- Home

- Ewan Lawrie

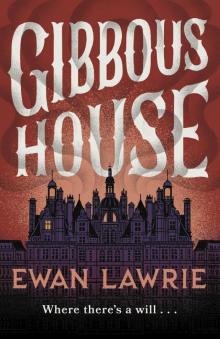

Gibbous House

Gibbous House Read online

Ewan Lawrie spent 23 years in the Royal Air Force, 10 years in Cold War Berlin and 12 years flying over the rather warmer conflicts that followed. He began writing during long boring flights over desert countries, and what started as a way of killing time soon developed into a passion.

Nowadays he spends his time in the south of Spain, writing and teaching English to Andalucians and other hispanophones. Though he has had stories and poetry published in several anthologies, Gibbous House is his first novel.

Gibbous House

Ewan Lawrie

This edition first published in 2017

Unbound

6th Floor Mutual House, 70 Conduit Street, London W1S 2GF

www.unbound.com

All rights reserved © Ewan Lawrie 2017

The right of Ewan Lawrie to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

No part of this publication may be copied, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

While every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material reproduced herein, the publishers would like to apologise for any omissions and will be pleased to incorporate missing acknowledgements in any further editions.

Typeset by Ellipsis Digital Limited, Glasgow

Cover design and illustration by Mark Ecob

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78352-089-3 (trade)

ISBN 978-1-78352-161-6 (ebook)

ISBN 978 1 78352 111 1 (limited edition)

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

‘He has no identity; he is continually in for – and filling – some other body’

John Keats in a letter to Richard Woodhouse, 1818

Dear Reader,

The book you are holding came about in a rather different way to most others. It was funded directly by readers through a new website: Unbound. Unbound is the creation of three writers. We started the company because we believed there had to be a better deal for both writers and readers. On the Unbound website, authors share the ideas for the books they want to write directly with readers. If enough of you support the book by pledging for it in advance, we produce a beautifully bound special subscribers’ edition and distribute a regular edition and e-book wherever books are sold, in shops and online.

This new way of publishing is actually a very old idea (Samuel Johnson funded his dictionary this way). We’re just using the internet to build each writer a network of patrons. Here, at the back of this book, you’ll find the names of all the people who made it happen.

Publishing in this way means readers are no longer just passive consumers of the books they buy, and authors are free to write the books they really want. They get a much fairer return too – half the profits their books generate, rather than a tiny percentage of the cover price.

If you’re not yet a subscriber, we hope that you’ll want to join our publishing revolution and have your name listed in one of our books in the future. To get you started, here is a £5 discount on your first pledge. Just visit unbound.com, make your pledge and type gibbous10 in the promo code box when you check out.

Thank you for your support,

Dan, Justin and John

Founders, Unbound

Chapter One

I had no sooner buried my wife than I received a summons to the reading of her late uncle’s will. Truth told, I was not a man brought low by grief. Numb and distant, perhaps, but three long years of watching death’s shadow hover had sucked the compassion from my soul. I was not aware of any inheritance that Arabella might have expected, but a trip to the Inns of Court in London seemed a pleasant diversion.

I was walking through the kind of fine rain that falls with more insistence than any thunder shower. The streets were wet as the mud smeared, like a noxious dubbin, on my boots. Carriages slurped past me, and the cries of street vendors were muted by the moisture in the air. I turned into Hawthorne Lane. Number 15 was not in the best of repair; only the stout, studded door seemed to have received any maintenance in the past few years: the timber was oiled, the handle and knocker gleaming in spite of the weather. A brass plate fixed below the knocker read: ‘Bloat & Scrivener’.

I was not even to meet with a partner, as the lawyer’s letter instructed me to ask for a Cartwright, sans titre. I gave the door a firm rap with the knocker. Scarce had I loosed my grip but the door opened.

‘Moffat.’

It seemed neither question nor invitation. The speaker drew the heavy wooden door aside and motioned with his eyes, and I followed him into a dark, narrow hallway. The gloom inside was dispiriting. Sconces held unlit candles, and the faint smell of damp decay lingered even after I brought my ’kerchief to my nose. I followed my less than garrulous guide down the corridor. He stopped abruptly and dealt a murderous blow to a door that seemed ill-prepared to receive it. Then he turned the knob with a delicate twist of his fingertips and melted away.

‘Come in, come in,’ came the enthusiastic, reedy cry. ‘Ye’ll be Moffat, then.’

I recognised the Scots accent of my native Edinburgh, though mine own had long since faded away. His was a most peculiar voice: high-pitched, with unexpected modulations, as if a moderate student of the bagpipes were practising on his chanter. No less odd was the appearance of the man himself. He might have been of middling height had his lower limbs not revealed the effects of a childhood diet like that of the worst slum-dweller. His head was uncommon large; the forehead bulging forth made his hairline seem to recede, though it plainly did not. I warrant that looking directly down at his head from above would have revealed an elongated oval. His nose was hooked and his chin curled up, as like to meet it. Were it not for the striking blue innocence of his eyes, he would have been the very image of a singularly malevolent Mr Punch.

He introduced himself as Cartwright, though of course I had guessed as much. Wishing me good morning, he pushed a meagre pile of papers fastened with a grubby, once-red ribbon in my direction.

‘Thaire ye are, it’ll aw be thaire.’

‘But, Mr Cartwright—’ I began. ‘It’s Cartwright, naw but Cartwright.’ ‘Well. Let it be so, but I understood there was to be a reading of a will?’ ‘And for why? When ye are the only fellow these papers consairn? And ye’ll no be reading them here!’ he added curtly.

With that he ushered me out: laying not a finger on me, he propelled me all the way into Hawthorne Lane as if by the force of the will under his enormous brow.

To my chagrin, if not to my surprise, the rain still hung mistily in the air. Two boys running towards the Wig and Feather careened into my person. It was all I could do to preserve my dignity and balance. I checked my pockets and my purse. Only my half-hunter was missing. I wished the thieves well on it, for the watch had told no time since my wife had become ill. Some may think me at once sentimental and callous, for though I had wound it not once since the day she took to her bed, I let it fall to thieves without a second thought, and this only one scant week after her death. Both charges I will not countenance. I had my reasons, though I do not care to share them. At least not yet.

I hailed a hansom cab and cursed the inclemency of the weather once more as the nearside wheel slurried my boots and trews.

‘Cheapside, The Chaste Maid Inn,’ I said as I settled in the seat. The driver’s grunt was eloquent and bespoke a premium on the fare. As much for the indesirability of my destination as the elegant cut of my cloth

es, no doubt.

‘A rare place, sir,’ the driver said gruffly as we arrived.

‘Rare enough,’ I allowed, paying in coin.

‘You’ll not find another such in Cheapside.’ The bark of his laugh was echoed by the crack of his whip and I was forced to leap clear of the carriage to avoid the splashing mud.

Be assured that places like The Chaste Maid were, in fact, none too rare in many parts of London. Its custom comprised the rough butchers and slaughtermen of the Shambles and the more rakish of the commodity brokers from Goldsmith’s Row: young blowhards in search of women who made mock of the hostelry’s name. My room was cheap, as it needed to be: I had made nothing of my modest means in the years of my wife’s illness. Capital needs growth and I had tended mine but poorly.

Passing through the public bar, I noted Thackeray, the landlord, hugger-mugger with two hulking brutes who appeared to know little of either silverside or silver trading. The staircase at the rear was dark and unwelcoming, but it led to my room and I took it at a gallop. The bed was little more than a cot and the remaining furnishings were as ill-matched as the load on a totter’s van. I threw my topcoat and hat on the stained bedding and rummaged in the coat for the red-taped packet of papers.

They were varied: several folded sheets of good vellum, two of the new-fangled lozenge-shaped ‘envelopes’ for the Penny Post and one curious parchment with a broken wax seal. The parchment was clearly an older document, though none appeared new. The Penny Post had delivered the two envelopes to Bloat & Scrivener over a year ago. I sat on the cot, pushing the soaking topcoat toward the bolster. I had no intention of remaining another night.

Unaccountably, I trembled as I opened the parchment. It bore the palsied hand of the aged, the tremors marring the cursive beauty of the copperplate. I began to read.

It being the year of our Lord 1838 Anno Domini, and I, Septimus Coble, of Gibbous House, Bamburgh, Northumbria, being of sound mind, do make this my last will and testament, voiding all and any extant or anterior wills and codicils.

I do leave all my possessions in sum and total to the husband, should there be any such person, of my great-niece Arabella Cadwallader née Coble, on condition that said party do move himself and all chattels to reside in Gibbous House without delay on being apprised of the contents of this my last will and testament.

Signed and sealed by Septimus Coble in the presence of:

Jeremiah Bloat

and

Cartwright

This 27th day of February 1838 Anno Domini.

I felt sick to my stomach. I could be rich, but at what price? The proximity of Northumbria to Edinburgh filled me with dread. Border country.

Coble’s will had dropped from my hand and lay like a discarded playbill on the rough planks of the floor. I picked it up, folded it carefully into a crisp square and hid it in the lining of my hat. The Penny Post letters drew my eye: I recognised the hand on one. The rounded, feminine curves and the idiosyncratic angles of the descenders and ascenders were indubitably those of my late wife, although I had not seen her pick up a pen in the last two years of her invalidity. I tore the letter from its cover. The handwriting was less sure, no doubt, than in her days of robust health, but the very fact of it was a facer indeed. I began to read.

Esteemed Mr Bloat,

I have received word from a confidential source that you may be in possession of some information that could prove to be to my advantage in the fullness of time. Should it be within your power and not constitute any breach of faith, trust or confidentiality, would you apprise me of any expectations that I may have?

I regret, as I am an invalid, that I am unable to attend your chambers. Therefore I petition you most respectfully to reply at your convenience,

Cordially yours,

Mrs Arabella Moffat, née Coble.’

Laying it to one side, I picked up the other. A masculine hand, also recognisable; I had but moments ago read its owner’s last wishes concerning the disposition of his legacy. I drew the letter from its enveloping lozenge; if it had been read more than once, it had been treated with extraordinary delicacy. The missive began abruptly, without salutation or preamble. Whether it was read by Bloat, Scrivener or, God’s grace, Cartwright, was therefore unknown:

Be in no doubt, I hold yourselves responsible should my great-niece be so misguided as to believe I hold her in any kind of affection. Whence she knows of any legacy, I should be most gratified to be enlightened, as your lawyerly selves were left in no doubt by mine own instructions as to the extreme confidentiality of this matter. I urge you not to enter into any correspondence with Mrs Arabella Cadwallader née Coble, on pain of a suit on which I should have no hesitation in expending my not inconsiderable fortune.

Coble

The queasy feeling in my abdomen was no mere hunger pang. I thought only of the name Cadwallader, by which – to my knowledge – my late wife had never been known.

Chapter Two

Sustenance was necessary, even though my appetite had vanished, leaving only a bitter taste in my mouth. I shook out my topcoat and laid it out to dry on the floor by the draughty sash window. The letters, and the blank sheets of vellum, I placed in a pocket of my frock coat. Picking up my hat from the bed, I looked at my ageing attire in the cracked cheval and repaired to the public bar.

Thackeray’s confederates were nowhere to be seen and glad I was of it. The man himself was behind the counter dispensing a pint of porter to a broker who seemed altogether too young for his impressive whiskers. The same observation could not have been made about mine host. He was a man, as we were wont to say then, in the prime of life: his whiskers put one in mind of J.C. Loudon’s most extravagant feats of topiary. Less aesthetically pleasing was his shirt, which had long abandoned any pretension to a state of whiteness. It was heroically stained and, no doubt, scented by the fruits of his labour. This garment, which would have been commodious for the majority of humanity, strained to hold in his paunch. It was not blessed with a collar, and by dint of a nod to the custom of wearing a cravat, was topped off by a filthy looking rag.

He addressed me in his usual servile fashion, which, though no trace of insincerity showed in his mien, aroused in me a sense of being ridiculed.

‘Mister Moffat, ’ow may I be of service? Porter, claret, gin for the... gentleman?’

‘I’ll have a plate of chops, Thackeray, and some honest beer.’

It was ever thus. Thackeray had no reason to think of me as anything less than a gentleman. However, he lost no opportunity to slight me by pause or intonation. My circumstances did not allow me to make protest or restitution, though I sorely wished they did.

I seated myself at the table furthest from the door. The landlord himself brought me a pewter tankard, which he filled from a pitcher of beer. From past experience I knew my comestibles could arrive post haste, but would more likely come at Mrs Thackeray’s convenience, which was to say none too soon. Eurydice Thackeray filled the role of cook in The Chaste Maid and never was a cook more inconvenienced by the prospect of culinary duties. Despite her euphonious name, Mrs Thackeray was more oak than nymph and she certainly reminded no one, least of all Thackeray, of a sweet maiden.

Through the inn’s grubby window, I caught sight of one of the brutes who had been speaking with Thackeray earlier. He peered through the square of glass, fixed me with a malevolent eye and gave me, I swear it, a savage nod and a wink such as Jack Ketch might give Mr Punch.

I should like to say the reverie with which I filled the wait for Mrs Thackeray’s inconvenience concerned plans to spend my newfound wealth, or of fond memories of the wife who had brought me such unexpected fortune. But it behoves me to confess that I spent the time, and I know not how long it was, ransacking my past for the faintest trace of a Cadwallader.

Even without the dubious benefit of their leathery flesh, the stripped bones of my lamb chops hardly covered any less of my platter. I tossed some copper coins on the trestle top and resolved to

quit The Chaste Maid to take some air. Halfway to the door, I reconsidered the prospects of an improvement in the elements and mounted the stairs once more to recover my topcoat. To my surprise, it no longer lay before the window. Indeed, it was absent altogether. All too present were the bedclothes, strewn as they were about the room and garnished with the few items of personal clothing I had left in the scabrous tallboy next to the cheval mirror. One of the brutes had been spying on me through the window before I began eating. Thackeray would provide some answers, I hoped. I threw up the sash window and looked down at the street outside. It appeared that come dusk a lamplighter would be searching for his ladder.

In the public bar, the landlord was smearing a tankard with a rag as filthy as the one adorning his crop. He lifted his chin in acknowledgement of my regard.

‘Mr Moffat,’ he said.

‘Thackeray,’ I rejoindered, and held his eye in the hope of provoking discomfiture.

In a few moments, he rewarded me with a grudging, ‘I’ll send the missus up. All right?’ He lifted his eyebrows at me.

‘Indeed, it is not all right. Who was he?’

He ran a finger around his neck for all the world as if he had a collar on his shirt.

‘The both of them were Peelers, sir. What could I do?’ For once it seemed his deference was genuine.

‘Could they not have used the stairs, man?’

‘Sergeant Purewipe and Constable Smackle were both in the Runners before. Out of Bow Street. Old ’abits die hard, Mr Moffat.’

‘What did they want? Did they say?’

For answer I received only a shake of his head and a look of pity for the ninny who would ask such a question in expectation of any answer. I lifted a salute of sorts to the brim of my hat and wished him good day.

Mercifully, the rain had stopped. Steam rose from the mud in the streets, and the day was bright and clear, as were the sounds of London itself. Still intent on a walk to clear my head, I braved the mud and the street vendors and headed toward St Paul’s.

In the Mouth of the Bear

In the Mouth of the Bear A Story a Week

A Story a Week Gibbous House

Gibbous House